Across the nation, family dinner tables have become war zones, friendships have been stress tested and dustbin men kidnapped and composted alive. Well, maybe we exaggerated that last one slightly. Hyperbole aside, the zero waste discussion is often a very heated one. Which by the way, is exactly why we chose that provocative title. As is so often the case, the more contentious the issue, the more we should probably discuss it openly. So, how about we tease out that precarious jenga block and get into this fiery topic?

We think that any movement towards more sustainable lifestyles is generally a fantastic thing, but we’re also not entirely convinced that a completely zero waste lifestyle is really possible, or even necessary. Before smartphones get hurled at walls in outrage, perhaps we can list a few different perspectives that we’ve come across.

We’ve probably all encountered a zero waste extremist. Someone who likes to rant about the frivolous excesses of consumer culture, condemning everyone but themselves as a bunch of lazy so-and-so’s.

You may have also come across the cynical views, that the zero waste movement is a fad or a fashion statement. A narcissistic form of cultural signalling, which when decoded, reveals an isolationist and idealistic perspective. Yes darling, we do high brow analysis here too, you know.

In opposition, many zero waste advocates make the point that small individual efforts can be multiplied to have a large collective impact. Grassroots action has to start somewhere, so why hate on people who are choosing to take personal responsibility and make an effort? After all, what are YOU doing to help make a difference for our planet?

Perhaps zero waste proponents have a simple elegant point; stop buying it and companies will stop producing it.

Thinking Bigger

One of the major reasons that the zero waste lifestyle has become a popular sub-culture in some nations, is the global plastic waste epidemic. While plastic is not the sole concern of zero waste supporters, it is often seen as the most detrimental and so we shall take a look at this material in particular.

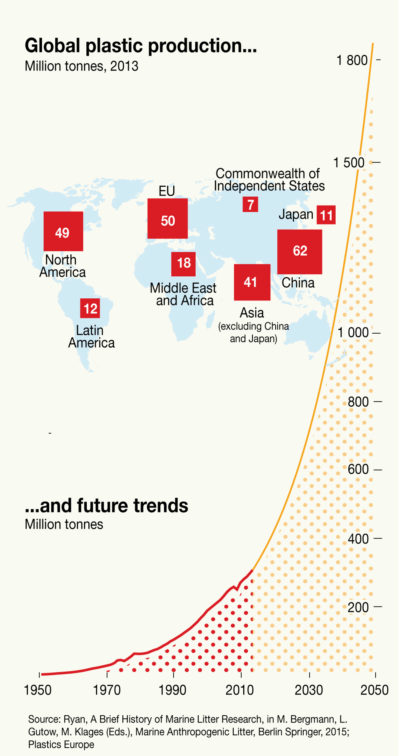

Many countries around the world are developing rapidly and plastic consumption continues to rise. The main contributor to plastic waste is packaging. By 2015, packaging accounted for around 35% of global plastic production and was responsible for close to 50% of global plastic waste that year. Millions of tonnes were also used in construction, textiles, consumer products and many other industries too.

Plastic has been consumed heavily by western nations and in recent years, countries like India, China and other Asian nations, with large populations, have also become huge consumers of plastic too. Plastic production has risen almost every year since the first synthetic plastics were created around a century ago. Some estimates show annual plastic production to have reached around 350 million tonnes in 2017 and annual production of plastics is forecast to increase over the next few decades.

How we deal with plastic waste problems is very different around the world, ranging from indifference, to zero tolerance of certain items like plastic bags. Some nations may be less inclined to position environmentalism as a primary concern because they may have other immediate priorities and challenges.

This may appear to be an irresponsible attitude and from an environmentalist perspective it is, but it is nonetheless a reality. It could also be considered somewhat hypocritical for one society to chastise a developing nation for actions that the former has practiced itself. In any case, collectively finding better solutions to old problems is probably more productive than simply pointing the finger at others.

So what does this all have to do with zero waste? Well, zero waste lifestyles are sometimes criticised for representing a drop in the ocean. If you compare the impact had by all zero wasters vs the size of the global problem, this is a somewhat reasonable analogy. Thinking globally forces us to acknowledge that there are many other factors to consider when strategising a species-wide drive towards sustainable living.

Even large scale initiatives such as the impending EU ban on single use plastic in 2021 is not forecast to dramatically interrupt the increase of global plastic production, which is set to rise for decades. Furthermore, although much of the worlds plastic is produced in Asia and increasingly consumed there too, a zero waste lifestyle is probably not something likely to be adopted by billions of people across Asia anytime soon.

It is also a factor that while packaging and consumer products make up a significant amount of plastic waste produced, millions of tonnes are also produced for other industries. Therefore separate solutions must be considered to address separate use cases.

So does that mean we should be defeatist and just do nothing as consumers? Certainly not! We do think that cultural movements can successfully help to change sentiment in societies. A shift in sentiment, can result in a change in consumer demand. The impact had by the BBC’s Blue Planet documentary is a great example of how making people more aware of an issue can change sentiment. This can then impact consumer demand and it is one spoke in the wheel of change.

People making an effort on an individual level, is definitely a positive thing. We should all accept a level of individual responsibility as consumers. However, to understand what a truly global solution could look like, many other things must be taken into consideration.

Zero Waste Doesn’t Exist in Nature

Everything in nature changes form and that usually results in some kind of byproduct. What is considered waste from one perspective, may be thought of as a valuable byproduct from another perspective. Animals devour the most nutritious parts of plants or prey, leaving behind peel, stalks, or carcasses. Trees release oxygen as a waste product. At a molecular level, atoms lose electrons, which are used by other atoms and new chemical compounds are formed.

Are you feeling like you’re back at school in a science lesson yet? Food chains, the human body and the functioning of our entire biosphere depends on waste in some form or another. What one species considers to be waste, may provide food and sustenance to other lifeforms. It’s a system that appears to have worked rather well for millions of years.

Zero Waste is a Bad Choice of Words

Some people argue that declaring yourself ‘zero waste’ is hypocritical. Most of us have electricity in our homes, the production of which currently results in some form of waste product. We also drive cars, use public transport and engage in countless activities that generate some form of waste.

But wait, perhaps you are sat there thinking “No no no, I walk or ride my bicycle everywhere”. Unfortunately you are still directly responsible for waste in the form of your worn out shoes or bicycle tyres. Plus we shouldn’t forget all those extra calories that your active, healthy body is metabolising, which eventually results in, you guessed it, more waste. Fortunately, the latter disappears down a magic bowl, never to be seen again. It’s biodegradable, but it’s still waste.

Not All Waste is Equal

We have focussed on plastic because the global issue with this material has become so glaringly obvious. Unlike many other materials that we find on earth, certain types of plastics take a very long time to break down and change form. Many naturally occurring waste materials end up as food for micro organisms, but that is often not the case with plastic.

If plastic is left to the elements, it is eventually broken down into smaller chunks by weathering. Although certain types of plastic can be eaten by micro organisms, this only happens with very specific types of plastic and in very specific conditions. Although this does give hope for future developments.

Major causes for concern are that waste plastic can often be destructive to animal life. Many types are not broken down effectively by natural processes and some can leech chemicals. Even if plastics are weathered down into tiny pieces, microplastics become a concern because we simply don’t know how they might affect various ecosystems. We know that microplastics have already entered many food chains and we are essentially conducting a huge science experiment to see what the outcomes will be.

The type of plastic and the environment it is disposed into, determines whether a plastic can be expected to leech chemicals or how long it will take to break down into smaller pieces. With that in mind, some angles we can approach this problem from are:

-The amount of plastic that already exists.

-The amount of plastic that will be produced in future.

-The types of plastic that we produce.

-The products we choose to use plastic for.

-The way we process plastic waste.

How Nature Deals With Waste

The air we breathe is made up of around 21% oxygen. As we all know, mammals exhale CO2 and this waste gas is processed on a vast scale by trees and other plants such as algae, which in turn produce oxygen as a waste product.

Now hypothetically speaking, if the world’s estimated 3 trillion trees, decided to halt the excretion of waste oxygen, it could be detrimental to other species. On the flip side, air with an oxygen content that is too high could also have a detrimental effect on mammals, because too much oxygen can also be harmful. Hopefully our lanky friends won’t start making drastic decisions anytime soon.

In a similar way, many excessive byproducts from human industrial endeavours can be harmful to species, including humans. The sensible approach then is surely to manage the type and quantity of waste that is produced. The term zero waste infers that it is possible to completely eliminate any given waste product. But surely the type of waste is just as important as the quantity of waste?

By understanding the balance and limitations of natural systems we can attempt to regulate the type and quantity of substances that we expect natural systems to produce and reintegrate. One example of this is the management of forests to ensure that adequate numbers of trees are planted to offset wood consumption and then managing the decomposition process responsibly by composting.

We’re definitely not saying that throwing waste plastic into landfill is ok, although we have all done it, be honest. Rather, we are presenting the view that finding ways to integrate our waste with natural processes, is probably a good idea. It may be more complicated in practice, but if nature can process waste efficiently and elegantly, then it’s not impossible.

Materials like plastics are unusual because they have existed for a very short time in earth’s history. Therefore there is no natural symbiotic process that has evolved on a large enough scale, to break down the massive quantities of this new material.

Interestingly though, some species of funghi have been shown to consume plastic, which might help to offer future solutions.

Minimal Waste is a Better Description

We think that much of the antagonism surrounding the zero waste movement is probably simply caused by the term, zero waste. In practice, most of the main ideas behind the lifestyle seem to be compatible with the clear and present need to manage our waste more effectively. Unfortunately, ’We need to manage our waste more effectively’, doesn’t have the same catchy ring to it and doesn’t make a memorable book title.

Potato skin can be called a waste product if you don’t eat it. Putting it on your compost heap just means that you are repurposing what you consider to be waste. To the microbes that will consume it, it is not waste, it is food. Therefore making compost and calling it part of the zero waste lifestyle is a bit of a misnomer. You are still generating waste, just managing it more effectively.

Work With Nature Not Against It

Nature has many of its own destructive and regenerative processes, such as the advance and retreat of ice stores, wild fires, storms, flooding and draught. Our human endeavours to manage societies and activities around natural phenomena, seem to be most synchronous when we understand and accept the immense natural forces that govern our world.

As humans we are part of the whole ecosystem but we have seemingly gained increased abilities to act more independently from it, in both creative and destructive ways. Creation and destruction are like two sides of the same coin and they are forces which recur in nature perpetually.

So how do we remain harmoniously integrated with this natural system yet maintain our mastery over it?

If we align our behaviour with everything else in nature, it becomes apparent that waste and byproducts are a natural phenomena. We have to strive to ensure that we manage the waste that we produce and find ways for waste to be made useful. If we take this approach when selecting the materials to use for the items we produce, we can likely integrate our human activity more successfully with existing natural processes. An example of this is biodegradable materials.

Recycling is Great

We’re yet to be convinced that it’s possible to maintain a lifestyle where you produce zero waste. However, reducing waste by managing resources more efficiently is a realistic proposition. Part of that efficiency can certainly come from recycling some materials.

Aside from an end product itself, recycling can also offer efficiency improvements to the overall production process of some products. However it is also important to consider that some materials, particularly plastics, can only be recycled efficiently a limited number of times before they start to loose the key properties that make them fit for purpose.

Access to adequate and efficient recycling infrastructure for different types of materials is also something to consider.

Reusable is Great

Getting the maximum number of uses from any item just makes sense.

It is however important to note that there are countless situations where single use products are more practical or sometimes essential. For example, it is simply practical for dustbin liners to be single use items. It is also important that some products used by medical professionals, such as gloves, are single use.

There are usually multiple ways to solve a problem, so we are hopeful that better solutions to these two examples, will continue to be developed. Biodegradable dustbin bags are a simple yet impactful way that a product can be improved by changing the material it is made from. For most people, this is probably a more convenient solution than scrubbing the dustbin each time you empty it.

We should also bear in mind that although one person may keep and reuse a product for years, at some point that product will still reach the end of its serviceable life. Eventually it will still wear out or stop being useful. With over seven billion people on earth, a lot of reusable items will still end up being thrown out at some point. Reusable or not, having a plan to manage an items eventual disposal, still matters.

So in the many situations where it is reasonable for items to be reused, great. Most of us have kitchen cupboards full of items that we expect to use multiple times. Even Greeks know that plate smashing should be limited to special occasions.

Multiple Solutions

In summary, we think that a strictly zero waste lifestyle is probably unfeasible for most people, but we do think that minimising non useful waste makes complete sense. For those that have tried to cut out as much personal waste as possible, we salute your effort to take personal responsibility.

Some materials can be utilised by being recycled, some materials can be reused and other materials biodegrade well. There is no single solution to our environmental waste problems, but a variety of ways to responsibly manage resources.

Collectively, we can have some control over 3 key things:

-The type of waste materials we create and consume.

-The amount of waste materials we create and consume.

-The way we process waste materials.

Who can influence these 3 variables?

Consumers

Behaviour, culture and demand are created and perpetuated by people.

Media

The flow of honest, accurate information to enhance public awareness is essential.

Universities, Institutions, Military

Developments in science, from various organisations, can offer new innovative materials and processes.

Businesses

To fulfil demand, companies supply products and engage in direct or peripheral activities.

Investors

Banks, funds, countries, organisations and individuals, deploy capital to support business activities.

Governments

Legislation either supports or discourages activities.

NGOs, Charities, Think Tanks

Many influential non government organisations conduct the insightful research necessary to inform solutions.

We think that complex problems usually require collaboration and input from various parties. Pointing the finger at one thing, group or organisation, probably won’t solve the problem.

Final Thoughts

Zero waste is one example of a lifestyle choice where action on an individual level can contribute to wider solutions by affecting culture, sentiment and demand. As a result we do think that the movement has had a positive impact. The direct impact may be small, but a knock on effect is that taking action creates a conversation, which is perhaps more impactful than the action itself.

The term zero waste however, is probably the main cause of contention surrounding this topic, because it is a little bit misleading. In the strictest interpretation, absolute zero waste is not possible. The name also suggests that a zero waste ideology might be more focussed on the quantity of waste rather than the quality of waste.

This is an important distinction because we think that in many cases, products made from biodegradable materials can offer great solutions. Both quantity and quality of waste are important because they affect our ability to manage it.

On a global level there are many things to consider when building sustainable societies, such as better materials, efficient management of resources, consumer demand and government policy. All these aspects are related and they all play a part in developing achievable, innovative and lasting solutions.

So, that’s our humble perspective and we certainly don’t claim to know everything, so if you don’t agree we’d love to hear your view. Let us know by commenting below or on social media.

Sources

Journal – Nature: Mapping Tree Density at a Global Scale

Article – National Geographic: Planet or Plastic?

Article – Smithsonian: Chow Down on a Plastic-Eating Fungus

Article – Global Plastics Production

Article – Plastic Oceans: MEPs back EU ban on throwaway plastics by 2021